The Harvest: This Week in Rural China – Dispatch No. 6 (16 January 2025)

Addressing Snow Tourism, Aquaculture Innovations, and Rural Governance Challenges

Welcome to this week’s edition of The Harvest, your weekly dispatch from This Week in Rural China.

One of the major stories we’re covering this week is the ‘Deep Blue 2’ salmon farming project in the Yellow Sea, which represents a significant step in China’s drive for greater food security through high-tech aquaculture. However, we ask critical questions about its impact on coastal communities and its long-term sustainability. In addition, we turn our attention to the cadres deployed across rural China as part of the government’s rural revitalisation programme. While state media tout their successes, we examine the structural issues that persist within this top-down model and the challenges communities face in adapting to such interventions. We also explore the growing “snow and ice economy,” driven by the government’s push to boost winter tourism and sports as a means of diversifying rural economies, and the ecological costs of this rapid expansion.

As always, we welcome your thoughts and reflections. Please feel free to comment below or email: nathan@thisweekinruralchina.com.

We hope this week’s dispatch offers valuable insights into the dynamic and often overlooked changes taking place in rural China.

Winter Harvest in the Yellow Sea: A Critical Look at Qingdao’s Salmon Farming Project

On 12 January, Workers Daily reported on the “Deep Blue 2” (深蓝2号) salmon farming project based in Qingdao, which is being celebrated as a significant breakthrough in China’s efforts to farm cold-water species like salmon in its warmer coastal waters. Located 130 nautical miles off the Shandong coast, the project harnesses the natural cold-water currents of the Yellow Sea, maintaining temperatures ideal for salmon cultivation. The 71.5-metre submerged structure, designed to operate autonomously with minimal human intervention, is equipped with advanced feeding systems and underwater imaging technology to replicate the salmon’s natural habitat, aiming to maximise both production efficiency and fish welfare.

The initiative is framed by state media as a success, claiming it will reduce China’s dependence on foreign seafood imports and provide healthier, locally produced options. However, use of the word “success” raises questions, particularly when examined in the context of its broader implications. While the project may indeed contribute to a more self-sufficient marine protein supply, its impact on rural revitalisation and local communities is less clear. The project is far offshore, meaning that the primary benefits will likely be realised by high-tech, specialised sectors rather than the broader rural population.

This raises concerns about the economic and social outcomes for coastal communities, which are not directly involved in the project’s day-to-day operations. The jobs created are likely to be in technologically advanced fields, but whether these will meaningfully benefit traditional fishing communities remains uncertain. If the project does not engage these local populations effectively or invest in surrounding coastal regions, claims of rural revitalisation are questionable at best.

Moreover, while state media tout the potential for healthier, locally produced salmon, this assertion requires more scrutiny. The shift towards domestic salmon farming might reduce reliance on imports, but the health benefits are far from guaranteed. Aquaculture, particularly in large-scale, closed systems, often raises concerns about fish welfare, environmental degradation, and using chemicals like antibiotics. While the “Deep Blue 2” project may alleviate some risks associated with traditional open-water farming, its impact on the surrounding marine ecosystem, local biodiversity, and the long-term sustainability of such farming practices remain areas of concern.

The environmental and ecological risks of intensive aquaculture are often downplayed in state-driven narratives about technological innovation. While the project is hailed as an example of sustainable marine agriculture, questions about its energy consumption, the quality of water used in the farming process, and its potential to contribute to the overexploitation of marine resources in the Yellow Sea should not be overlooked. While high-tech solutions are often framed as environmentally friendly, these claims frequently obscure significant ecological trade-offs, as seen in projects like ‘Deep Blue 2.’

Ultimately, the “Deep Blue 2” project, while a remarkable technological achievement, reflects a broader trend in China’s agricultural development towards high-tech, large-scale solutions. While it may increase seafood production, the benefits for rural communities, particularly those engaged in traditional fishing practices, remain uncertain. The true test of the project’s success will be whether it provides tangible, long-term benefits to these communities and whether it can sustainably coexist with the environmental realities of the Yellow Sea.

Cadres on the Frontlines—A Critical Assessment

This week, state media have praised the work of the 500,000 cadres deployed across rural China as part of the government’s rural revitalisation programme. People’s Daily and other outlets have heralded these “village first secretaries” (驻村第一书记) for driving improvements in infrastructure, employment, and poverty alleviation in rural areas. In regions like Gansu, Guizhou, and Anhui, reports highlight how cadres have provided support during medical emergencies, navigated agricultural setbacks, and helped villagers secure jobs.

While these narratives present a picture of success, a closer look at the realities behind the headlines is necessary. The cadre system remains a top-down model, with officials from provincial and municipal levels tasked with overseeing rural development. This structure often sidelines local agency with interventions that may alleviate immediate challenges but fail to tackle deeper, systemic issues such as land ownership, resource access, and long-term economic sustainability.

The frequent rotation of cadres every few years further complicates the picture. Each new cadre must re-establish relationships with the community and understand its unique challenges. The short-term nature of their assignments hinders the continuity of development initiatives and trust-building between residents and authorities.

In addition to the structural issues raised by the top-down nature of the cadre system, the successes trumpeted by state media often ignore the broader consequences of specific interventions led by cadres, such as tourism. For example, promoting tourism as a key economic driver in Guizhou has displaced some villagers to make way for hotels, resorts, and other tourist infrastructure, often with inadequate compensation. The land that once supported agricultural livelihoods has been repurposed for commercial ventures, leaving many without the means to sustain themselves. In many cases, the cadres themselves have financial interests in these developments, further exacerbating local inequalities and creating a conflict of interest.

While tourism has undoubtedly brought new economic opportunities to the region, including jobs in the hospitality and service sectors, these are often low-wage and seasonal, offering little security for residents. As a result, the influx of tourists has raised living costs and increased housing prices in rural areas, making it difficult for villagers to afford basic necessities.

While state media laud the cadre system as an overwhelming success, the lived reality for many villagers tells a different story. The reality is one of displacement, rising costs, and the erosion of traditional ways of life. This raises important questions about the broader consequences of such initiatives and whose interests are indeed being served—the state and its cadres or the rural communities that are the supposed beneficiaries of these policies.

Reforming Agricultural Innovation: A New Evaluation System for Rural China’s Scientific Talent

On 13 January 2025, China introduced a significant shift in its scientific evaluation system, with significant implications for agricultural research and rural revitalisation. The new model, which de-emphasises traditional academic metrics such as publications, focuses instead on recognising researchers’ practical contributions, particularly in agricultural development. This reform can reshape how talent is nurtured and recognised in rural China, a critical area for sustainable farming and resource management efforts.

Historically, scientific careers in China have advanced based on academic publications and accolades. However, for researchers like Xu Aiguo, a scholar at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), this system failed to capture the true value of their work. Xu’s research on digital soil mapping, which has had tangible impacts on agricultural productivity, went largely unrecognised under traditional evaluation metrics. Under the new system, however, contributions such as Xu’s, with direct real-world applications, are now more likely to gain the recognition they deserve, offering a more holistic path for career advancement.

This reform is particularly significant for rural areas, where the application of scientific research directly affects the livelihoods of millions. It aligns with China’s broader rural revitalisation efforts, offering greater recognition to innovations that address pressing challenges such as food security, environmental sustainability, and technological advancement in agriculture.

These reforms, while promising, must contend with significant challenges in ensuring that local communities, particularly those in remote regions, benefit from this shift. The true measure of success will depend on fostering sustainable, grassroots innovation and ensuring that the new evaluation system does not merely reinforce existing power structures within the scientific community. Moreover, its implementation at the local level will determine whether it can deliver genuine improvements in agricultural practice and rural well-being.

China’s Ice Economy Heats Up Amid Rural Revitalisation Push

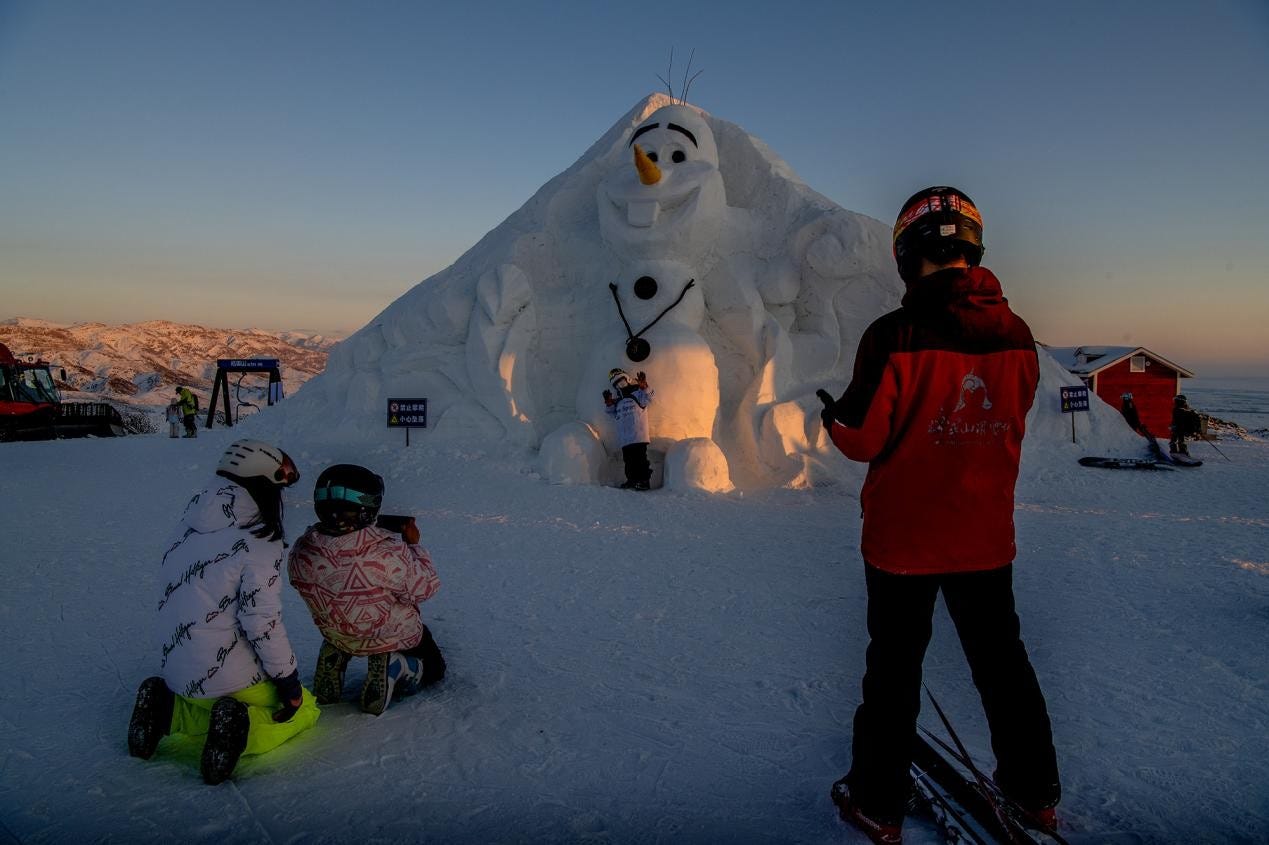

This week, China’s “ice and snow economy” (冰雪经济) continues to gain momentum, reflecting the growing importance of winter tourism and sports as key drivers of rural revitalisation. Building on the belief that “ice and snow are invaluable assets,” the government has launched an ambitious initiative to engage 300 million people in ice and snow sports. This effort has transformed once-overlooked snowy landscapes into powerful economic engines, especially in rural areas.

The rapid expansion of winter sports and tourism has significantly changed rural communities, particularly in provinces like Heilongjiang and Jilin. These areas have developed state-of-the-art winter sports facilities, attracting domestic and international tourists, generating employment opportunities. In addition, regions less traditionally associated with winter sports, such as Hunan, Sichuan, and Shandong, have begun tapping into their snowy terrain, hosting ski events and snow-themed festivals. For instance, Hunan now boasts resorts near Changsha and has hosted annual snow festivals, while Sichuan promotes winter tourism around Mount Emei, including ski competitions and cultural events.

This “ice and snow economy” also intersects with China’s broader environmental goals, with the government positioning winter tourism as a vehicle for sustainable development. However, the claim that economic growth from snow tourism and environmental sustainability can seamlessly coexist is debatable. While tourism brings increased revenues, rapid infrastructure expansion—such as ski resorts and seasonal facilities—can lead to environmental degradation, from deforestation to water usage concerns in snowmaking processes. In regions like Jilin and Heilongjiang, the snow economy has already prompted concerns about the ecological impact of such large-scale developments.

Despite these challenges, the economic transformation of snowy regions focuses on boosting tourism revenues and creating new industries that can sustain long-term prosperity. This diversification of rural economies offers an alternative to traditional agriculture, providing rural communities with new income sources and contributing to broader economic growth. The question, however, remains whether this shift can be maintained sustainably in the face of environmental and social pressures.

Government Allocates 80 Million Yuan for Disaster Relief in Tibet Following Earthquake

In last week’s edition of This Week in Rural China, we reported on the 6.8-magnitude earthquake that struck Shigatse, Tibet and examined the significant challenges facing the region, from underdeveloped infrastructure to the vulnerability of local buildings in the face of seismic events. Following that report, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs have now allocated 80 million yuan in emergency funds to aid recovery efforts. These funds will be directed towards restoring agricultural and livestock operations, rebuilding infrastructure, and providing vital recovery supplies.

While immediate financial support is important for helping affected areas recover, it raises questions about the broader and longer-term response. The allocation, while a necessary step, may not be as swift or comprehensive as state media suggests, given the region’s systemic challenges and its ongoing vulnerability to natural disasters. The logistical and technical hurdles presented by Tibet’s high altitude, remote location, and fragile infrastructure mean that rebuilding efforts will require continued support and strategic planning.

As discussed previously, Tibet’s infrastructure is ill-equipped to handle the demands of natural disaster recovery. Many roads are impassable during winter months, and existing buildings often fail to meet modern construction standards. While the government’s quick action to provide emergency funds is a step in the right direction, this disaster underscores the need for long-term investments in infrastructure improvement, disaster resilience, and building regulations. Simply addressing the immediate aftermath is not enough—the focus must now shift to strengthening Tibet’s ability to withstand future crises.

The 80 million yuan emergency relief is just one part of the equation. A comprehensive, sustainable recovery strategy must involve improving the region’s infrastructure, ensuring robust disaster preparedness, and addressing the deeper structural vulnerabilities that leave Tibet’s rural communities exposed. Only with sustained investment and attention can Tibet reduce its vulnerability to future disasters and begin to build a more resilient future.

Between Mountains and Waters - Photo of the Week for 16 January 2025

Harnessing the Sun in Rural Shanxi

This drone photograph from Xuezhang Township, Ruicheng County, Shanxi Province, captures a photovoltaic power station emblematic of the region’s shift toward renewable energy. Nearby, the ancient Qingquan Temple in the scenic Wang Mountain area of Shenxi Village stands as a reminder of the region’s rich history. Together, these sites illustrate the juxtaposition of ancient traditions and modern technological advancements shaping the landscape of rural China. (Photo by Zhan Yan/Xinhua)