In 1979, Edward Said introduced the world to Orientalism, a groundbreaking theory that would reshape how we think about the West’s portrayal of the East—by examining how Western writers and scholars depicted Arab cultures, Said exposed a pattern of prejudice, stereotyping, and misrepresentation—one that still sparks debate and discussion to this day.

When Edward Said tackles the concept of the "Orient," he quickly makes a critical point: it is not an absolute, physical place. Instead, the "Orient" is a label—a construct that stretches across cultures, geography, and history. Said argues that this term exists only because the West has defined it in opposition to itself. In other words, the Orient is less about the actual East and more about the West's self-image and place in the world. This creates a sharp division between what is considered "indigenous" or "authentic" and what is deemed "alien" or "other." These distinctions feed into broader categories, such as the enlightened West versus the barbaric East. What is important to understand, Said points out, is that this vision of the Orient does not exist independently; it exists only in relation to the West. The concept is built on Western perceptions, sweeping across political, cultural, and historical boundaries, often oversimplifying and lumping together a vast diversity of people and places. This reductionist view, Said argues, is the core of what we call "Orientalism."

The term Orientalism refers to a “Western European (male) representation of the East or Orient, an us-them dichotomy on a global scale and justification for colonial domination” (Harrell et al. 142–143), which had initially consisted of an enabled collective consisting of colonial scholars, writers and artists. These culturally privileged and enabled could present cultural works based upon their experiences in the Orient to the naïve majority at home in the West who had little exposure to any Oriental cultures. This monopoly of representation led to the widespread dissemination of what Said was careful not to refer to as myths or lies but as a symbol of European power over the Oriental peoples and their discourse. Though initially prevalent in the colonial eras of Britain and France, Orientalism, as defined by Said, is certainly not confined to the colonial era but one which lives on today in the representation of the East. In discussing the 20th Century, Said writes:

“Yet with what greater harm has the twentieth-century version of the myth been maintained. It has produced a picture of the Arab as seen by an “advanced” quasi- Occidental society. In his resistance to foreign colonialists the Palestinian was either a stupid savage, or a negligible quantity, morally and even existentially. According to Israeli law only a Jew has full civic rights and unqualified immigration privileges; even though they are the land’s inhabitants, Arabs are given less, more simple rights: they cannot immigrate, and if they seem not to have the same rights, it is because they are ‘less developed.’” (306–307)

The relationship between these prejudices and the forming of public opinion and political policy throughout the West is seen as hugely pertinent by Said, and it is central to his arguments against the notions of Orientalism. Said asserts that these declarations of what makes dominant, overpowering voices made the Orient with little or no resistance from the Oriental world. This lack of resistance, therefore, enabled an uncontested, generalised portrait of a large portion of the world to emerge. This is well described by Said in his opening pages, stating that the perpetrators of this Orientalist thought were able to dominate because;

“In a quite constant way, Orientalism depends for its strategy on this flexible positional superiority, which puts the Westerner in a whole series of possible relationships with the Orient without ever losing him the relative upper hand. And why should it have been otherwise, especially during the period of extraordinary European ascendancy from the late Renaissance to the present? The scientist, the scholar, the missionary, the trader, or the soldier was in, or thought about, the Orient because he could be there, or could think about it, with very little resistance on the Orient’s part.” (7)

In summary, Orientalism categorises many cultures, religions, peoples, nations and customs into one single scholarship based on their exclusion from the boundaries of what the dominant Western voice conceives as the familiar and the alien. As Said puts it, “a dynamic exchange between individual authors and the large political concerns shaped by the three great empires.”

Orientalism Transferred to Modernity and Contemporary China

In the opening paragraphs of Said’s introduction, he described Orientalism as an all but entirely European invention due to the European’s proximity to the Orient, its colonial claims and its experiences within the so-called Orient. Said’s words strictly relate to the division of the world into the East and West. As for the origins of Said’s Orientalism, this may be true, but in practice, the theory may be applied elsewhere.

As already discussed, one of the critical concepts of Orientalism that Said repeated was the absence of a voice on the part of those defined as Oriental by the West. However, it is highly questionable whether Edward Said’s proposition is relevant today. The book Orientalism was published in 1979 when China began its journey of massive reformation and came out of a somewhat dark and isolated period. With the death of Mao Ze Dong, the Chinese saw the opening of their doors to the outside world and certain degrees of freedom handed back to the people and cultural icons/intellectuals regaining their pedestals to a limited extent as social, political and economic reforms were made. Another vital factor to consider is the rapid growth of the Chinese economy and, therefore, the nation’s significance on a global scale. Couple this with increased movement of people through cheaper, more accessible air travel to and from China, accessibility of the internet and a global media intent on reporting every second of every day, and it does not take a great deal of effort to assume the Chinese have gained a greater voice, mobility and understanding of western perceptions. This leads to greater access to the Western sphere whilst the West’s naivety and ignorance regarding knowledge of China has also decreased, indeed taking something away from Said’s traditional rendering of Orientalism being so one-sided.

While China may have gained a say on the world stage, it is imperative to point out that this still fluctuates greatly depending on the region, wealth, status and, to a greater degree, separation of society and state. This is one reason we must consider China in these terms as a regional state. Typically, this would mean the wealthier, mainly coastal urban regions with a majority Han population with access to higher education standards and better connection to the outside world would almost certainly have a greater voice than those belonging to rural minority ethnic groups in the more impoverished areas of China.

With this conflict of competing voices, one much louder than the other, surely Edwards Said’s notions of Orientalism can help analyse the unbalanced voices of China today. Considering the nation of China and its fifty-six officially recognised ethnic groups, which are spread throughout this vastly disparate nation, there are many similarities between Edward Said’s discussion and the interaction of the Chinese people. This more recent discussion of Orientalism perpetrated by the Orientals has become termed “self- Orientalism”.

An unfeasibly large undertaking to discuss in one article, this concept must be further broken down. In my attempts to replicate this self-orientalism in the most precise possible manner, I have decided to discuss this topic in the light of Ethnic tourism in China. This is partly because of my previous studies in tourism but also because Ethnic tourism is a particularly poignant issue which allows us to see a separation of people on an economic and social basis.

It is also a relatively recent and growing way in which the more affluent and ‘enabled’ Chinese of burgeoning urban China can interact with their more bucolic, poorer countrymen. In this article, I will argue that Edward Said’s notions of Orientalism can be applied to a contemporary domestic Chinese example whereby Chinese nationals comprise both Occidental and Oriental models of Ethnic tourism in China

“Ethnic tourism is defined as that form of tourism where the cultural exoticism of natives is the main tourist attractant. It involves complex ethnic relations and a division of labour among three groups: tourists, tourees (natives who, literally, make a spectacle of themselves), and middlemen (who mediate tourist-touree encounters and provide catering facilities).” (Van den Berge 234)

Since the death of Mao Zedong and the subsequent opening up of China and some withdrawal from ideological politics that saw tourism as a symbol of bourgeois existence, the tourist trade has seen a progressive swelling of activity in both domestic and international tourism. Within China and elsewhere, ethnicity and culture are often used as “major tourism assets and are often marketing themes for destinations where they are found” (Henderson et al. 530). As China is a nation of fifty-five ethnic minorities and one Han majority ethnicity, this is a mainly established and widely practised version of tourism. Li Yang clearly defines the Chinese urbanites as the main perpetrators of such tourism in China and declares that:

“Seeking the sublime and exotic minority life is a trend common among middle-class consumers. Peripheral regions like Yunnan have been imagined as a mysterious frontier and ethnic groups are portrayed as ‘primitive’ living a ‘pre-modern’ and ‘backward’ life.” (582)

This quote is particularly brilliant in drawing comparisons between Edward Said’s idea of Orientalism and the modern Chinese experience of Ethnic tourism, which we will return to in more detail later. However, we must first establish that there is another side to Ethnic tourism, which varies significantly from other more conventional types of tourism because it is “based on the conflict between the dominating government’s intent to control the unassimilated ethnic tribes and the tourists’ motivation to experience authentic and marginal ethnic cultures.” (Dong et al. 165–166). It is this issue of control or power which is dominantly discussed in the field of ethnic tourism and one which overlaps with Edward Said’s notions of Orientalism.

Whether or not Ethnic tourism profoundly affects the ethnic and cultural authenticity of a region or people may depend on how the tourist responds to the marketing of various villages and cultures. We have learnt from the above definition that people travel to ethnic tourism sites to experience a lifestyle and practices different from their own, which is widely supported by a more specific reference to China by Li Yang in her matrix of definitions. We have also seen that Ethnic communities, as with all tourist sites, may be open to manipulation by outside forces to attract more tourists. This could be a particularly poignant issue in China as all but a few backpacking/niche tour operators are either state-owned or heavily linked with state-owned travel organisations. It is also widely asserted that the promotion of ethnic cultures has long been at the heart of the Chinese government’s plans in order to promote China’s image as a multicultural nation-state. This mix of tourist desire for experience and government or business desire for profit could be a driving factor in contemporary self-orientalism in the twenty-first century.

Applying Ethnic Tourism and Self-Orientalism in China; Authenticity vs. Cultural Commoditisation

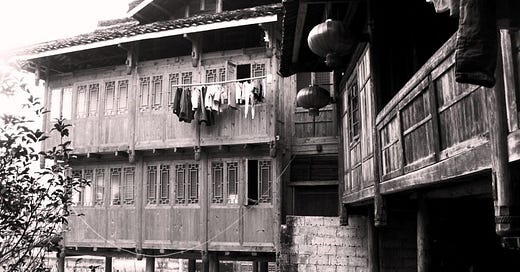

It is now commonplace in China to see ethnic minorities presenting themselves in traditional dress to perform shows and sell goods as a means for gain. From my experiences in Hebei and particularly Guangxi, these practices are more than just selected villages taking part in organised tours catering to government initiatives and travel agents’ contracts. Tourism has become a grassroots industry, and recognising that cultural identity (however authentic) is a means to make money has grown momentum.

According to Li Yang, tourism hosts and producers work together to “package culture and present staged representations”, which can cause people to alter their “lifestyle, architecture and other aspects of culture”, creating an inauthentic image. This is the general premise of Orientalism, though it differs from the traditional example as it appears as an intended manipulation of the truth as opposed to misinterpretations by a dominant voice. However, the issue of dominance is still an apparent factor.

In discussing the canonisation of Ethnic identities concerning Orientalism, it is essential to first look at how tourists are drawn to Ethnic tourism. One of Edward Said’s critical notions was that textual construction was the main factor in the creation of the Orient. Said says, “The idea, in either case, is that a book can always describe people, places, and experiences, so much so that the book (or text) acquires a greater authority and use, even than the actuality it describes”. Regarding Chinese tourism, we can look at this factor concerning how such tourism is promoted through the likes of travel marketing publications and media.

Marketing tourism is unquestionably a tool for selling an attractive product by stimulating a customer’s interest. However, the flip side could be more obvious: the message portrayed to a customer through the language and imagery that a piece of marketing uses to attract a customer. Edward Said referred to this in his discussion of cultural tools in the 19th Century that were used to create an image of the Orient. This is just as relevant in the twenty-first Century as Edelheim points out in his 2007 work on the polysemic reading of tourist brochures:

“If only a specific view of a nation is presented to travellers purchasing holidays to domestic destinations, and alternative views — while existing, but not visible — are closed out, then it can be reasonably argued that those brochures are tools constructing an overriding understanding of society.” (8)

Evidence such as the brochures and admissions tickets for the Stone Forest County near Kunming shown in Seductions of Place (Carter and Lew 253) present pictures of women dressed in traditional costumes playing traditional musical instruments with a backdrop of mysterious rock formations rising to the sky beneath the moon and above bonfires and mist. The author also suggests replicating a place of “feminized ‘others’ and a place of ethnicity and equitable power relations” (253). This analysis is not at all dissimilar to Said’s impression of the Western perception of a “separateness of the Orient, its eccentricity, its backwardness, its silent indifference, its feminine penetrability” (206) or the “great Asiatic mystery” (44).

Staying in Yunnan, a quick look at the ‘Third Kunming International Tourism Festival’ poster reveals a similar image. This time, an entirely female crowd stand in great numbers, linking hands and reaching to the sky. In close examination, we can see the faces of older women and men reaching the sky but almost completely masked by the much younger, more beautiful women standing dominantly in front. They are all elaborately dressed in eye-catching outfits and headdresses, with not one of them looking remotely similar. Again, The backdrop is a scenic medley of high mountains and nature, which has been pieced together using photo editing software. This example is one of the common trends in presenting ethnic minorities as people who have never stopped singing and dancing and inviting tourists to take a chapter from the great album of ‘nationalities’ with the same sense of cultural recognition as they would a famous mountain.

Whilst Said’s notions talk of the heavy influence of travel literature and travel guides in manufacturing Orientalism, these glossy posters and catalogues published by tourism promoters have outweighed guidebooks in the significance of tourist awareness in China.

Since Said’s discussion of early nineteenth-century Orientalism, many new mediums of representation have occurred. The most dominant medium to emerge is the advances in film, and this has played a considerable role in promoting tourism through television and more innovative ways, such as the arrival of TV screens on buses and trains.

The Chengde Tourism Administration distributes its free DVDs of Chengde’s Highlights. Throughout the thirty minutes of the film, we see little of the people of Chengde. Instead, we get representations of the Kangxi era and invitations to participate in traditional Manchu wedding ceremonies and banquets. A young lady dressed in traditional Manchu clothes stands by the central lake of Bishushanzhuang, playing a musical instrument in remarkable resemblance to the advertisements for South Central China, Yunnan-based tourism which is so far away (geographically and culturally) from the Northern reaches of Hebei Province in North Eastern China.

These images are replicated in two books on Chengde, which, amongst many images, show flamboyant displays with elegant females balancing on the heads of face-painted males and curious figures on horseback in the forest of Weichang County. Having lived for two years in Chengde, I can see little of the elegantly modest market town I came to know. In fact, in my experience, by visual recognition, you are more likely to encounter ethnically Uyghur or Hui Chinese (who are not native to the region) than any other minority. The visual remnants of the Manchu influence are all but gone, except for the elaborate restaurants offering the ‘exotic meat’ of the many stuffed wolves, camels and other unusual creatures littering the lobby as an incentive to step in. Of course, there are also the walled confines of the leading tourist site, the Summer Mountain Resort, where you may hand over your RMB for Qing currency to spend at the many market stalls offering suspicious-looking ‘artefacts’.

Further exploring Said’s notions of Orientalism, we can see that those under the label of ‘Oriental’ lack a voice and that amongst the mass representation of the Orientals by a foreign voice, “There is very little consent to be found”. Said continues beautifully in his description of Flaubert’s account of a young Egyptian lady:

“She never spoke of herself; she never represented her emotions, presence, or history. He spoke for and represented her. He was foreign, comparatively wealthy, male, and these were historical facts of domination that allowed him not only to possess Kuchuk Hanem physically but to speak for her and tell his readers in what way she was ‘typically Oriental’” (6).

Oakes discusses in Tourism and Modernity in China that there are many more reasons behind tourism development in ethnically diverse areas of China than regional economic development. Oakes describes the triumphant capitalist elite who have used tourism to explain China’s alternative road to capitalism encompassing Confucian values, which supposedly “adds up to more ‘humane’ capitalism” (41). Aihwa Ong also describes these Chinese business elites as a tool of capitalism through ‘Self-Orientalism’ (171). This all replicates Said’s notions that those with power and wealth will have a more significant say and means of control than those without it. In this case, that is to say, the interests of Ethnic tourism are not necessarily those of the Ethnic peoples.

Many studies have been undertaken on the authenticity of ethnic tourism in China, such as the study into two Miao Villages in Yunnan conducted by Joan Henderson et al. The most important about these two villages is that they were both under the wrath of tourism. Henderson et al. discovered that the perceptions of authenticity by the villagers and the tourists differed between the two villages. In summary, one village acted on behalf of preconceptions of what tourists wanted to see based on instruction from outside influences, and the other operated on instinct. The more inauthentic village was the village which had seen its decisions made on its behalf. This highlights a manipulation of culture to create an inauthentic image based on what people want to see.

However, perhaps more interesting is the tourist’s reaction to the survey, which suggests that at least 80% of domestic tourists possessed enough prior knowledge of the cultures to realise the inauthentic representation of the culture (534). This is significantly at odds with Said’s idea that those on the receiving end of Orientalist exposition did not know better (Said 25). Whilst on the one hand, the Chinese elite and the Chinese government may be trying to create an image of a united China, it has not escaped the eye of many commentators that Ethnic Tourism is a government priority to create local distinctiveness. Said’s claim that “Orientalism is a style of thought based upon an ontological and epistemological distinction made between “the Orient” and (most of the time) “the Occident.” (2) This is somewhat more in line with Said’s notions of an inevitable consequence rather than a planned manipulation of the truth, as Smith explains creating exoticism is central to the very idea of the host-guest relationship in tourism. Furthermore, this is another good example of the power relationship Said often referred back to, that argument being; “The underlying power relation between scholar and subject matter is never once altered: it is uniformly favourable to the Orientalist.”

Conclusion

Perhaps the most relevant and comprehensive definition of Orientalism for the contemporary Chinese example is already laid out for us in Edwards Said’s opening introduction of the book Orientalism. Said emphasised that Orientalism is;

“a whole series of “interests” which, by such means as scholarly discovery, philological reconstruction, psychological analysis, landscape and sociological description, it not only creates but also maintains; it is, rather than expresses, a certain will or intention to understand, in some cases to control, manipulate, even to incorporate, what is a manifestly different (or alternative and novel) world.” (12)

Said’s three fundamental notions, the textual construct of the Orient, the distinguishing between Occidental and Oriental divergence and the issue of dominant power have been constantly encountered when investigating the issue of Ethnic Tourism in China. This article has discussed how the prejudiced interpretation of scholars in Said’s nineteenth century also fits, albeit somewhat modified, into the realm of ethnic tourism in contemporary China.

We have seen how one group of people — the considerably richer, more enabled urban Chinese- have created an alternative world in rural ethnic villages, demonstrating a clear distinction between two opposing cultures, one dominant. This ‘Oriental’ world is not entirely imagined but indeed lived up to by its inhabitants under the implicit guide of their preconceived expectations of tourist interest. We have also seen how the involvement of the government and business elite has dictated the direction and image of many cultures in China; this has led to an inauthentic and manipulated culture.

In conclusion, this article further asserts Edward Said’s claim that Orientalism is not a mass misinterpretation or unwarranted generalisation but, indeed, the symbol of a world where one culture resides dominant over the other(s).

Bibliography

Bai Zhi Hong. Ethnic Identities under the Tourist Gaze. Asian Ethnicity. 8,3 (2007): 245–258. Print..

Carter, Caroline. Alan A Lew. Seductions of Place: Geographical Perspectives on Globalisation and Touristed Landscapes. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005. Print.

Chengde Tourism Administration. Chengde, China (Chengde Zi Sai Ming Zhu.) 2009. DVD.

Chu, Yiu-Wei. The Importance of Being Chinese: Orientalism Reconfigured in the Age of Global Modernity. Boundary 2. 2,35 (2008): 183–206. Print.

Dong, Er Wei. Ethnic Tourism Development in Yunnan, China: Revisiting Butler’s Tourist Area Lifecycle. Proceedings of the 2003 North-eastern Recreation Research Symposium (2004): 164–170. Print.

Edelheim, Johan Richard. Hidden Messages: a Polysemic Reading of Tourist Brochures. Journal of Vacation Marketing. 13,1 (2007): 5–17. Print.

Fung, Y H, Anthony. The Emerging (national) Popular Music Culture in China. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 8,3 (2007): 425–437. Print..

Guo Bao Tian. Travel in Chengde China. Chengde: Chengde Tourism Administration, 1997. Print.

Halper, Stefan. The Beijing Consensus. New York: Basic Books, 2010. Print.

Harrell, Stevan, et al. Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers. Hong Kong; Hong Kong University Press, 1996. Print.

Henderson, Joan, et al. Tourism in Ethnic Communities: Two Miao Villages in China. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 15,6 (2009): 529–538. Print.

Komlosy, Anouska. Procession and Water Splashing: Expressions of Locality and Nationality During Dai New Year in XiShuangBanNa. Royal Anthropological Institute. 10 (2004): 351–373. Print.

Lew, Alan A, et al. Tourism in China. New York: The Haworth Hospitality Press, 2003. Print.

Li Yang. Planning for Ethnic Tourism: Case Studies from XiShuangBanNa, Yunnan, China. Thesis. U of Waterloo. 2007. Web. 25th Novemeber 2011.

Li Yang et al. Ethnic Tourism and Cultural Representation. Annals of Tourism Research. 38,2 (2011): 561–585. Print.

Li Yang et al. Ethnic Tourism Development; Chinese Government Perspectives. Annals of Tourism Research. 35 (2008): 751–771. Print.

National Tourism Administration of the People’s Republic of China. Tourism Statistics. China National Tourism Administration, 2009. Web. 19 November 2011.

Nyiri, Pal. Scenic Spots; Chinese Tourism, the State and Cultural Authority. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 2006. Print.

Oakes, Tim. Tourism and Modernity in China. London: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Ong, Aihwa. Undergrounded Empires: the Cultural Politics of Chinese Transnationalism. London: Routledge, 1997. Print.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979. Print.

Shi Chi-You. Negotiating Ethnicity in China; Citezenship as a Response to the State. London: Routledge. 2002. Print.

Smith, Valene L. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 1989. Print.

Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China; Second Edition. New York: Norton & Company, 1999. Print.

Treiman, D.J. The “difference between heaven and earth”: Urban–rural disparities in well-being in China. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility (2011): 1–15. Print.

Van den Berge, Pierre. Tourism and the Ethnic Division of Labor. Annals of Tourism Research. 19 (1992): 234–249. Print.

Womack, Brantley. China between Region and World. The China Journal. 61 (2009): 1–20. Print. Yang Zhao Hua. The Best of Chengde. Shenzhen: Xueyuan Publishing House, 2000. Print.

I get it. I find it quite worrying how “western” viewpoints of “the east”, ie China, are usually from a western cultural perspective. Always trying to find parallels that make an easy to understand analogy. No, China is NOT like Russia… for example.